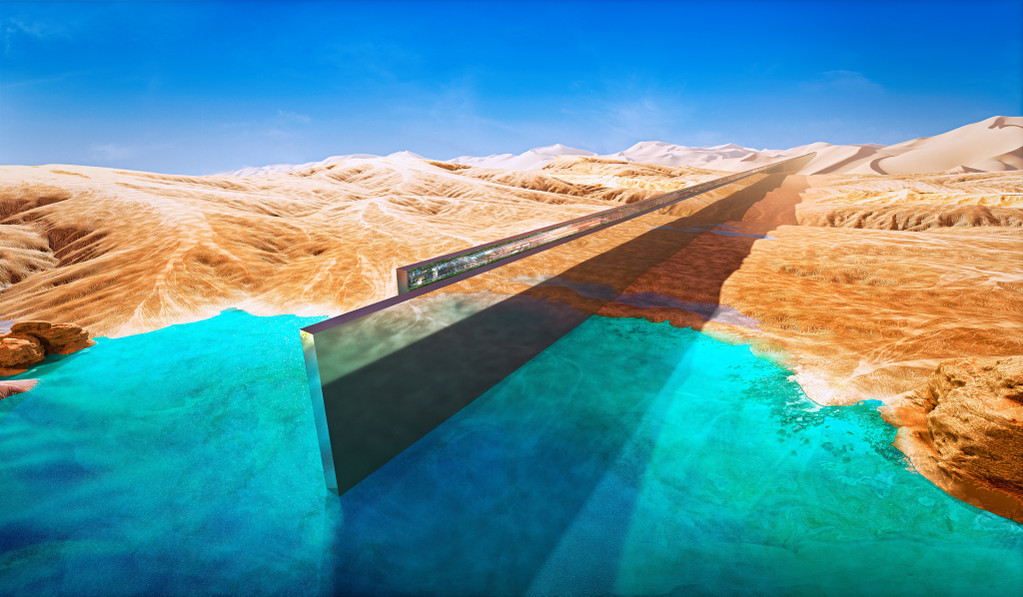

A revolutionary urban planning project is taking form in Saudi Arabia. The foundations of a city 170 kilometers long and a few hundred meters wide are rising from the desert floor, protected by mirrored walls that will reflect the exuberant surroundings to a height of 500 meters.

Trend

The Line and the dream of the linear city

10 August 2023

The concept of a linear city has been around for years, but for the first time one seems to be on the verge of actually being built. The Line – the name of the nascent city, also called NEOM – is being presented by the Saudi royal family as an urban dream with a cyberpunk feel, envisioned for the convenience of services – all available within a 15-minute walk from anywhere in the city – and the speed of communication: the city will be served by a super-fast train that will run through it from end to end in as little as 20 minutes. The project even has its own trailers worthy of a Hollywood blockbuster in which a voice accompanied by crescendoing orchestral strings whispers to us that "The design of the contemporary city is essential. What if we got rid of cars? What if we got rid of roads? What if everything you needed was just five minutes away?" The words accompany glossy images of a megastructure rising out of the desert, cleaving sand dunes and mountains into an urban strip poised to accommodate 9 million inhabitants by 2045. However, the feasibility of The Line is still unclear. To imagine how it might be, let’s take a look at some other linear city projects promoted by urban planners but never built. While it may sound like a dystopian nightmare to some, the dream of building a linear city has in fact appealed to generations of architects.

Linear cities in history

Spanish urban planner Arturo Soria y Mata was the first to propose this concept, and in 1882 he proposed the idea of an "almost perfect" city consisting of a 500-meter-wide urban strip, with services arranged on either side of a very long boulevard. His experiment was partly realized under the name Ciudad Lineal, an urban area later swallowed up by the sprawl of Madrid's suburbs. The idea of building a linear city was then taken up by Edgar Chambless in the early 20th century in the United States. On a map, the architect drew a straight line across the country from the Atlantic to the Pacific, passing through the Allegheny Mountains, the Mississippi River, and the Rocky Mountains. Along this line, Chambless envisioned a continuous strip of two-story houses built over three rail lines, with a rooftop promenade and vast green areas. This endless urban strip would be named Roadtown, combining the conveniences of the city with the beauty of the countryside. Chambless's vision embodied the U.S. idea of freedom and mobility, yet the concept of a linear city was also making inroads even among Soviet architects. Mikhail Okhitovich, a constructivist theorist, rejected the principle of a centralized city as a typical expression of capitalism, advocating the design of a city made in strips. In 1930, the Russian architect presented a linear evolution plan for the city of Magnitogorsk, envisioning a network of eight 25-kilometer-long vectors along which residents and workers would live in individual houses, with children relegated to separate spaces. Okhitovich's idea was not well received. Indeed, he was considered politically dangerous and executed in 1937.

Le Corbusier, Kenzō Tange and city-viaducts

Meanwhile, a superstar of French architecture, Le Corbusier, was also pondering the same concept. In 1931 the French government presented an urban planning project for Algiers in celebration of the centenary of colonial rule. Le Corbusier saw it as an opportunity to promote Plan Obus, an idea that was as futuristic as it was crazy that envisioned a huge elevated highway winding through the hills, with 14 stories of working-class housing crammed under the overpasses, a kind of viaduct-beehive capable of accommodating 180,000 people. Fortunately his ambitions remained on paper.In 1961, in Japan, architect Kenzō Tange presented his plan for the future of Tokyo Bay on TV. The plan called for an 80-kilometer urban spine across the bay, with modules connected by three levels of loop roads and buildings hooked to the highway skeleton. It was a system that could be expanded as needed. In his view, the structure of the modern city took the place of cathedrals: just as cathedrals were the center of the medieval city, so the new "civic axis" would shape the backbone of the metropolises of the future.

.jpg?scalemode=auto&quality=100?w=3840&q=100)

A city glittering with ceramics and hard as porcelain tiles

Aside from its promotional renderings, The Line will be a place to walk, sunbathe, and lie by the pool. It’s reasonable to imagine that ceramic and porcelain tiles will be an excellent option to clad it. Given the setting – desert and windy – the qualities of both materials – as strong as they are durable – make them ideal for cladding the exteriors of a man-made, futuristically elegant place. Ceramic tiles are dense and resistant to water, stains, and sunlight, and there are endless styles and finishes to choose from, making them perfect for creating designer solutions. Porcelain tiles are even more resilient due to their being pressed and fired at high temperatures. Perfect for the outdoors, we can already imagine them on the endless sidewalks of NEOM and framing the edges of swimming pools from the future. In fact, porcelain tiles stand up to abrasions, making them perfect for spaces that require durable flooring.We don’t know whether The Line will succeed or if it is doomed to fail like its predecessors, but we do know that with the right finishes its journey through time will certainly last longer. For now a thin line can already be glimpsed in the sand in the desert of northwestern Saudi Arabia.

.jpg?cropw=4096&croph=2654.2479700187387&cropx=9.695217308093677e-13&cropy=76.7520299812622&cropmode=pixel#?w=3840&q=100)

.tif?cropw=4036.303976681241&croph=2705.4159900062464&cropx=59.69602331875912&cropy=25.584009993753906&cropmode=pixel#?w=3840&q=100)

.jpg?cropw=4096&croph=2978.1919633562356&cropx=0&cropy=93.80803664376384&cropmode=pixel#?w=3840&q=100)

.jpg?cropw=4096&croph=2304&cropx=0&cropy=215.39045431878446&cropmode=pixel#?w=3840&q=100)